From The Narwhal, this a.m.:

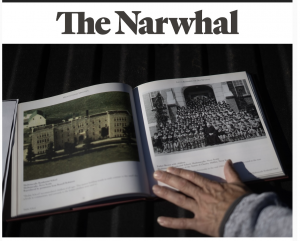

From The Narwhal Newsletter, Sep 30, 2025. One hundred and forty federally run residential schools operated across Canada for more than a century; so did dozens of other institutions run by other authorities, all designed to forcibly assimilate generations of Indigenous children. In 1997, the last school — Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet, Nvt. — finally closed its doors. But the traces of these institutions linger on the land, in derelict buildings, on street names like “Indian School Road” and in the makeshift memorials erected on former grounds: children’s toys, tiny shoes and offerings of tobacco and sweetgrass. What to do with this history? For the survivors of Shubenacadie Indian Residential School in Nova Scotia, the only federally run institution in the Maritimes, the decision was clear. “We want our descendants, and the ones that are to come to have a place to come learn about who they are … what our ancestors came through, [and] honour that, so that they can take that strength,” Dorene Bernard, who was among the last children to attend Shubenacadie, told The Narwhal. Freelance journalist Moira Donovan and photographer Darren Calabrese spent time with Dorene exploring the grounds of the former school, designated as a national historic site in 2020. Moira spoke with her and others about how survivors are leading the work of commemorating residential school histories. Not all communities want to see those histories commemorated in the same way, but honouring survivors is important — particularly as they age and pass away. Long Plain First Nation in Manitoba declared the Portage la Prairie Residential School a historic site in 2003, 17 years before the federal government officially recognized it as such. Former chief Dennis Meeches told Moira, “It’s important to remember where we came from, to learn from the residential school era and to make positive changes in life as our ancestors would have wanted us to do.” For a long time, many survivors were silent about what they endured at residential school; Tim Bernard, executive director of Mi’kmawey Debert Cultural Centre, didn’t even know his own father and uncle attended Shubenacadie until an Elder pointed them out in a class photo. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the first class-action lawsuit against the federal government was launched by a group of Shubenacadie survivors; their effort led to the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, the result of thousands of survivors bravely sharing what happened to them. Their courage deserves acknowledgement — in our memories, and on the land. Today, on the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, I hope you will read Moira’s story and reflect on the collective responsibility to keep history alive. Take care and don’t forget to look back, Michelle Cyca |