This page is a subpage of Bioeconomy

View that page for a list of related pages.

Page created Feb 2, 2026 by David Patriquin.

See Related Post, with summary.

2014 Clearcut on Crown land, viewed in 2015 (Google Earth). The oft-cited figure of “5.7 million cubic meters/annum” for the Sustainable Harvest Level for Nova Scotia was formulated in 2016, well before the Lahey Recommendations (2018) and the NS Government’s commitment (2021) to 20% Protection by 2030 (currently just under 14% of the NS landscape is protected), before major nutrient limitations were quantified, before losses of hemlock, beech and ash trees associated with exotic pests and before the record wildfires of 2023 and 2025.

CONTENTS

– Background

– On the origin of the 2016 estimate

– On historical harvesting levels

– More context

– New demands on the NS wood supply

– Conclusions

– On the work underway to develop a new number based on the triad model

– How about it, Premier Houston…

– Related

BACKGROUND

In a post on Sep 27, 2024 I asked “From whence came the figure of “5.7 million cubic meters/yr” as the Sustainable Forest Harvest Level for Nova Scotia?

On Oct 16, 2024, after some quibbling between industry and government contacts about whether the figure originated with industry or government, I reported that the NS Government had clarified that the figure dates from NS Government sources in 2016: see Nova Scotia Government responds … (Post, Oct 16, 2024).

In that response, the Gov. personnel commented

“Our analysis that resulted in this number predates our adoption of the triad model of ecological forestry. Work is underway to develop a new number based on the triad model.”

It’s now more than a year later. So when can we expect that new number? It is surely urgent, given the plethora of changes in the political and economic landscape of Nova Scotia since 2016 and many more “natural” stresses on our forests.

The following comments are revised/updated from those given in the Oct 16, 2024 Post

ON THE ORIGIN OF THE 2016 ESTIMATE

Screencapture of first 2 pages in the Forestry Economic Task Force’s Nova Scotia Forestry Sector Fact Sheet (Nov., 2023)

With all of the mega-projects that involve use of wood or clearing of forested lands that have been proposed, discussed, and some approved in NS recently, I had wondered where the oft-cited figure of “5.7 million cubic meters/yr” as the Sustainable Harvest Level for Nova Scotia* came from, and how it was generated.**

*e.g., in the NS Forestry Economic Task Force’s Nova Scotia Forestry Sector Fact Sheet (Nov 2023)

** View posts ….Sep 3, 2024: Questions about stakeholder meetings (re: Feasibility of a new paper mill in Queens Co.) and Sustainable Forest Harvest Levels in Nova Scotia

& Sep 17, 2024: From whence came the figure of “5.7 million cubic meters/yr” as the Sustainable Forest Harvest Level for Nova Scotia? 17Sep2024

I assumed it originated with the NS Government/DNR/L&F/NRR, now DNR. On Aug 24, 2024, I wrote two NRR research scientists, posing 8 questions about the number. They had been been helpful in the past when I had asked similar types of questions. This time however I was told that such inquiries must “go through Communications Nova Scotia.”

At one point Communications Nova Scotia told me that the figure originated with the Forestry Economic Task Force. My inquiries went back and forth between myself and Communications Nova Scotia and the NS Forestry Economic Task Force until Oct 8, 2024 when I received a reply from Communications NS that answered at least some of the questions:

| Apologies for the delay. We can provide the following and you can attribute it to the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables:

The department calculated the figure of 5.7M m3/yr harvest level in 2016. It appears in the 2016 State of the Forest Report (page 81) and we provided it for the National Forestry Database where it is listed under wood supply. The provincial total includes both Crown and private land. Our analysis that resulted in this number predates our adoption of the triad model of ecological forestry. Work is underway to develop a new number based on the triad model. In developing the 2016 number, we used: – protected areas data that was current at the time The Forest Economic Task Force conducted an independent analysis. It aligns with our calculation because they used the same base data as a stating point. |

As far as I am able to determine from documents produced by the Nova Scotia Forestry Economic Task Force (NSTEF) about their use of the number, their number originated with “DNRR”. It is specifically attributed as such in a document “Nova Scotia Forest Fibre Supply Analysis, Forestry Economic Task Force NOVEMBER 2022 – FINAL REPORT by AFRY AB”. That Report is listed under Reports & Analysis at nsfetf.com. I received it after requesting it on a form at the bottom of that page. (Legal language at the top of the report prohibits distribution of the contents.) There is no information in documents available from NSTEF or in my correspondence with NSTEF to suggest or confirm that “The Forest Economic Task Force conducted an independent analysis” as contended by Communications Nova Scotia.

ON HISTORICAL HARVESTING LEVELS

It is commented in the 2023 Forestry Economic Task Force Fact Sheet* that historical harvesting levels have been substantially below the Sustainable Harvest Level (cited as 5.74 million cubic meters per annum).

*Nova Scotia Forestry Sector Fact Sheet Published 2024, data for 2022. The equivalent document, Nova Scotia Forestry Sector Highlights, published in 2025, makes no mention a sustainable harvest level – does that mean a new estimate is on its way, or that it is now considered irrelevant?

That is simply not true. According to the NS Gov. Stats, harvests exceeded 5.74 million cubic meters per annum from 1996 to 2005 inclusive:

Chart 1. Historical Harvest Levels From Registry of Buyers of Primary Forest Products, 2022 Calendar Year | Report FOR 2023-1, Department of Natural Resources and Renewables September 2023. See Wood Supply (page on this website) for the actual values 1990-2020. “Forest age class data for 2003 showed a notable increase in the 0-20 and 21-40 years age classes compared to 1998, and decreases in the 61-80, 81-100, and 100+ age classes. This was attributed to increased harvesting on private land during this period which resulted in many older stands being replaced by young natural stands and plantations.” – From N. Ayer (2018) p30 citing the 2008 State of the Forest Report. Some of the peak in years 2004, 2005 was prob. associated with salvage harvesting following Hurricane Juan – see State of the Forest Report (April 2008) p. 9

The excess harvesting has come from the softwood rather than the hardwood component:

Chart 2. Forest fibre utilization rates in Nova Scotia. Screencapture of Fig 5

in Feedstock Availability and Cost in Nova Scotia By County and Specific Locations, FP Innovations and NS Innovation Hub, Aug 2021.

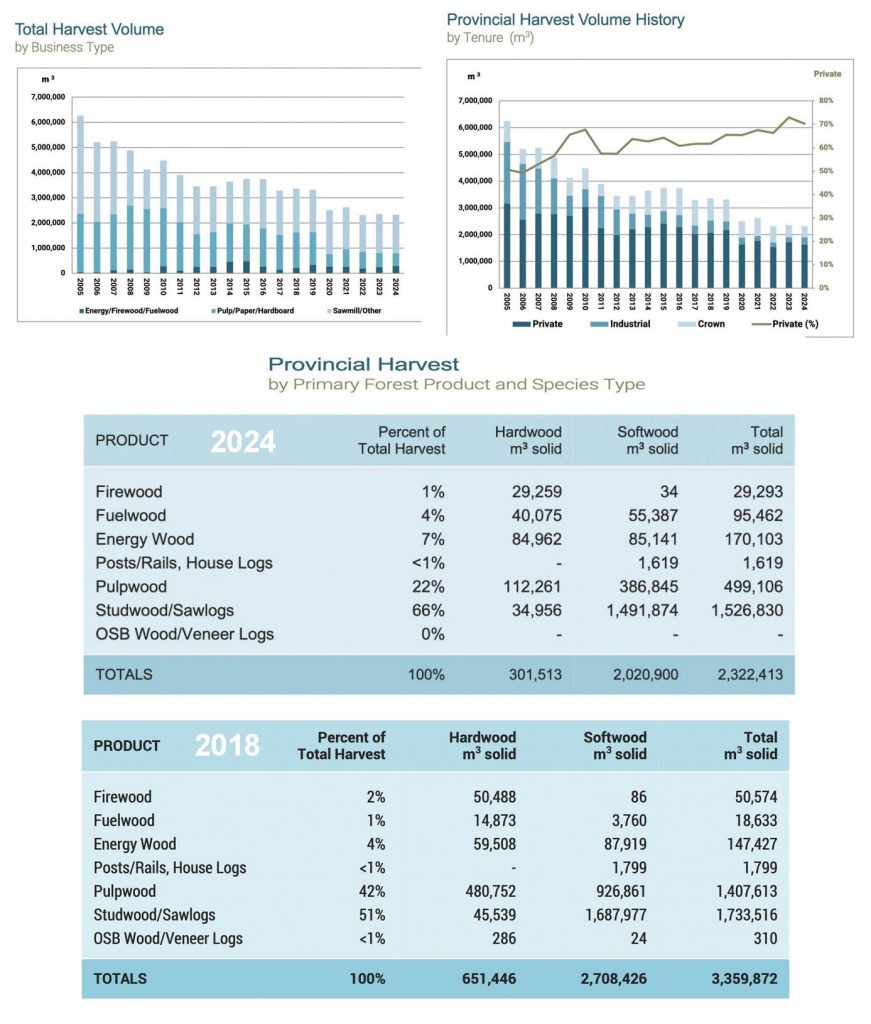

Charts in Fig 3. below show harvest volumes over time partitioned into Business Types, and Tenure; the Table shows Provincial Harvest in 2024 by Primary Forest Product & Species Type. Over time there has been a gradual increase in the percentage of volume from private lands (and a corresponding reduction in percentage from Crown lands, perhaps reflecting in part formal protection of some of the Crown lands). Major reductions in Pulp and Paper volume in 2012 and 2020 followed closure of pulp and paper mills (the top table shows data for 2018 before closure of Northern Pulp in 2020; and the lower table, data for 2024, well after closure).

Chart 3. Charts from the 2025 and 2019 Buyers Report

Top: Provincial Harvest by business Type Tenure

Middle: Provinical Harvest Volume History by Tenure

Bottom: Provincial Harvest by Primary Forest Product & Species Type 2024 and 2018

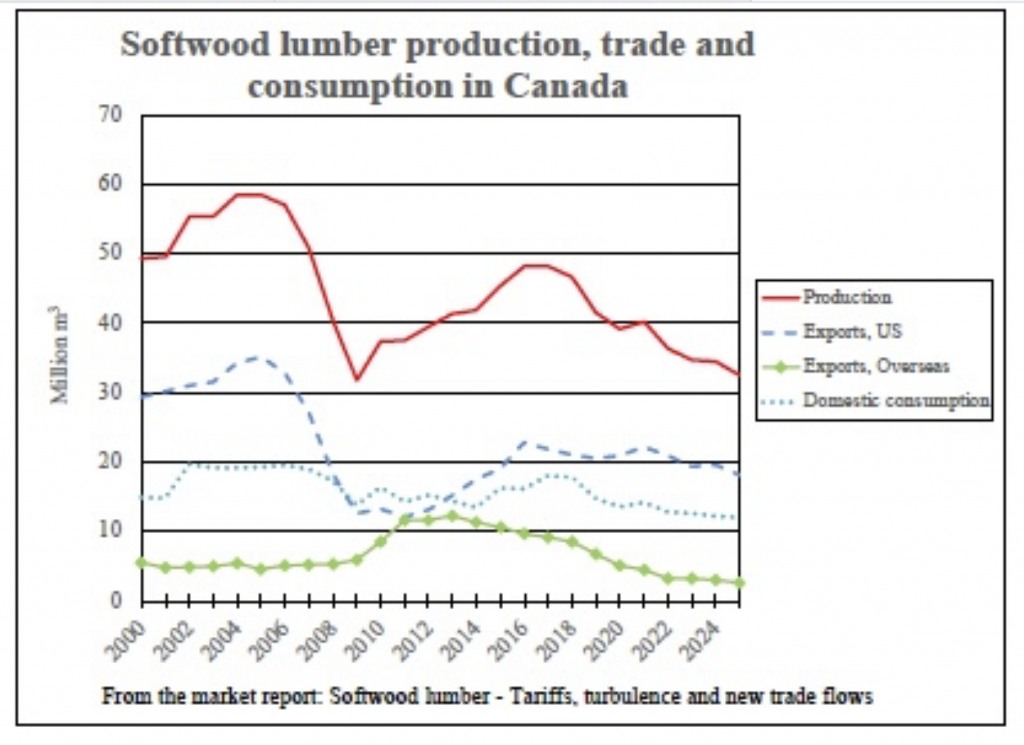

Chart 4 illustrates that the trends of reduction in softwood volumes over time for NS (Figs 2 & 3) also occurred for Canada at large.

Chart 4. Softwood lumber production, trade and consumption in Canada. From Canada’s lumber industry at a crossroads: Shrinking capacity and challenging market diversification, new outlook report finds

By: Håkan Ekström et al., on www.woodbusiness.ca, Nov 12, 2025 “Conclusions. Canada’s lumber and forest sector is expected to continue contracting through 2030. Sawmill capacity will decline, particularly among smaller and older operations in regions affected by insects and fires, and export patterns will slowly rebalance away from the US. Rural communities will bear the greatest impacts. If US tariffs are eventually removed, the surviving modern mills could benefit from improved margins as lumber prices are likely to increase in the US. Meanwhile, opportunities exist in gradually growing overseas markets and in the domestic construction sector, where housing starts would need to roughly double by 2035 to meet projected demand.Achieving that, however, would require policy changes, streamlined permitting, and lower construction costs – none of which are guaranteed.”

MORE CONTEXT

Against the backdrop of the trends illustrated by Charts 1-4 above above, it’s worth recalling or noting:

- Nova Scotia’s forests are among the most, if not the most, intensively harvested in Canada (data 1985 to 2011).

- Widespread public concerns about excessive and/or environmentally degrading forest harvesting in Nova Scotia led to and were validated by two reviews of forestry practices in the last 18 years: the Natural Resources Strategy (2008-2010); and Lahey’s Forest Practices Review (2017-2018).

- The lead-up to the second review was in years when the harvest levels were well below 5.7 million cubic meters per annum.

- There is significant uncertainty and anxiety in the forest industry about the impacts of the Triad on Crown land wood supply. Lahey & Co. predicted that with implementation of the Forest Triad there would be a transient reduction in wood supply from Crown lands of 10-20% [Lahey Report, Conclusion#64, p29] but Lands and Forestry Minister Iain Rankin indicated that he was not prepared to accept even a transient reduction in wood supply (view Post on NSFN Aug 20, 2020)

…And while Lahey predicted less clear cutting would lead to a reduction of Crown land wood supply of 10 to 20 per cent, Rankin disagreed. “We believe that we can sustainably grow this industry.” – CBC Dec 3, 2018

“We’re talking about leveraging higher volumes of that low-value pulp wood, both private and Crown land,” he said. “When those things are in place, then you’ll see more opportunity for partial harvesting on both private and Crown [land].” CBC, Aug 19, 2020

Forest NS folks also made it clear that they were not prepared to accept reduced supply from Crown lands, rather more lands would be logged to make up for any reduction in wood supply per unit area harvested – view NSFN post 22Jan2021. However, now that the Triad is “completed” (NS Gov News Release 17Jan2023) – or well on its way – the 10-20% prediction is proving to be valid regardless:

Theoretically, this new system will increase certainty of wood supply…But according to lead presenter Bevan Lock of Port Hawkesbury Paper (PHP)…the company…has faced a 17% reduction in its short term Crown fibre supply due to the implementation of the new ecological forestry model*.

*“Cited in Shifting into high gear“, article by David Lindsay in Atlantic Forestry Review Vol 32#2, Nov, 2025, pp 14-19. The article reports on presentations, discussions and activities at the Canadian Woodlands Forum held Oc8-9 2025 in Truro, NS. “The gathering was entirely devoted to high-production forestry, specifically in the context of Nova Scotia’s “triad” model.

-

- New US Softwood Tariffs are cited by Forest NS folks as additional reason to rapidly increase HPF (High Production Forestry) on Crown lands as it “allows us to remove higher volumes in a smaller area and reduce those costs of harvesting”*. *Comments made in How do we deal with the Softwood Lumber Tariff? a recent Forestry Uncut podcast produced by Forest NS.

- Following the record spring fires in NS in 2023 and in 2025 while the massive Long Lake fire was ongoing in Aug and Sep., Forest Nova Scotia folks were quick to comment that managed forests reduce the risk of fire and thence to argue that old forest in Protected Areas (or protected as Old Growth) require some forest management to reduce fuel loads and hence wildfire risk.* However, post-fire analyses of wildfires do not support the generalization that such management of older forests will reduce wildfire risk or intensity, in fact it may increase the risk of wildfire by drying out the understory.** (Obviously where old forest occurs in proximity to habitations and sources of ignition, extreme thinning or even total clearance of old forest as in Fire-Smart practices is appropriate.) *2023 fires, see – “The Crucial Role of Forestry in Preventing Devastating Wildfires”, post on Forest Nova Scotia Blog Page, Nov 16, 2023, and see Forest NS on wildfires, and some comments (post on this website). 2025 fires, see CBC Sep 4, 2025, article on glyphosate spraying. Comments Forest NS executive director Todd Burgess : “there is a short-term risk [associated with spraying] but… a managed forest is a lower fire hazard over the course of decades.” Also view comments by Steve Freeman in discussion elicited by CBC article “– Increase in wildfires shows forestry practices need to change, experts say”, Aug 29, 2025. Says Freeman, “Forest management is not the problem. It’s the answer.” ** View literature under Forest Management & Fire on this website,

- There is now, but there was not in 2016, clear evidence of widespread declines in avian habitat and populations in N.B. and N.S. associated with “forest degradation”/loss of Old Forest over the period 1985 to 2020 (Betts et al, 2022); it’s very likely that there have been significant habitat and population declines in other species groups associated with forest degradation, and the precipitous decline in Mainland Moose is well documented (view NS Gov: Mainland Moose).

-

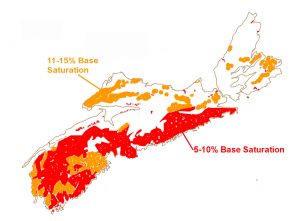

Chart 5: Sketch showing prominence of highly acidic, calcium-deficient/high aluminum forest soils in Nova Scotia. Sketch after Keys et al. (2016), Fig 3. View Soils /Calcium depletion /Acidification (on this website) for more about it.

Unlike most other areas in eastern North America that were affected by acid precipitation, soils and waters in NS have not recovered and/or are are very slow to recover following introduction of emission controls; currently circa 60% of our soils in forested landscape have severe calcium deficiencies. This limitation was not fully documented until 2016, and was not taken into account in the 2016 estimate.

- Post-2016, we have begun to experience major losses of particular tree species associated with exotic pests, notably Hemlock Wooly Adelgid, Beech Leaf-mining Weevil & Emerald Ash Borer.

- In 2023 and 2025 we experienced record wildfires associated with extreme spring drought (2023) and record-breaking summer drought (2025); forest ecologist Anthony Taylor advises* integration of hardwoods into mono-cultured or mostly pure softwoods stands to act as firebreaks.

*Maritime Noon Interview Oct 15, 2025; rough transcript here - The late summer wildfires of 2025 and perhaps into the future could be especially damaging to both short term and long term forest productivity and increase the risk of forests on the highly acidic, calcium-deficient/high aluminum soils in Nova Scotia transitioning to barrens.*

*Forest Soil Scientist Kevin Keys: “…there is indeed a risk of some nutrient-poor forested sites in Nova Scotia being damaged by fire to the point that that they could shift to heathland cover. The sites where this is most likely to happen would be ones where soils are very stony, shallow, and/or high in sand, so that available nutrients are already very low, and where acid rain and perhaps previous harvesting have further reduced nutrient availability. More frequent and extensive loss of forest floor nutrient reserves after fires on these sites could be the tipping point to convert the area to heathland…” KK in interview with Joan Baxter Dec 1, 2025 - In 2023, the spring wildfires were followed by record levels of precipitation and severe flooding in the summer of 2023. It is well documented that clearcutting can exacerbate flooding*, thus potentially reducing sustainable harvests levels when/where maintenance of the forest canopy is critical. *View paper by Robert L. France et al., 2019 pertaining to NS, and related literature listed under Watershed Level Management on this website.

- Post-2016, there has developed a broad consensus that we have global climate and biodiversity crises which require we all do our part, however incremental that might be. Based on conditions in NS, Lahey 2018 (p. iii) concluded that “protecting and enhancing ecosystems should be the objective (the outcome) of how we balance environmental, social, and economic objectives and values in practising forestry in Nova Scotia.”

- Surely with 75% of the NS landscape forested, we must at the very least ensure net sequestration of carbon by our forests. Evidently, that requires that we harvest less than 4 million cubic meters per annum (see figure below).

Chart 6. Forest harvesting levels and annual net change in forest ecosystem carbon in NS 2002-2013. From State of the Forest 2016 Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources

Renewable Resources Branch. Note that the carbon balances change from negative (forests are net emitters of carbon to the atmosphere) to positive (forests withdraw carbon from the atmosphere) when the harvest levels dropped to circa 4 million m3 per annum and below.Perhaps these data and the interpretation I applied are a bit sketchy scientifically, but they illustrate a point: Sustainable Harvest levels estimated based on only tree growth and standing stocks, i.e. looking at wood supply alone, may be much higher than harvest levels that allow net conservation or increase in total forest ecosystem carbon.* *Also view: High emissions or carbon neutral? Inclusion of “anthropogenic” forest sinks leads to underreporting of forestry emissions, D Bysouth, J Boan, JRMalcolm & AR Taylor, 2025, in Frontiers in Forests and Global Change; and “Congruent Long-Term Declines in Carbon and Biodiversity Are a Signature of Forest Degradation” by M.G. Betts et al., 2024 in Global Change Biology. The latter paper addresses N.B forests, but the conclusions likely apply to the more intensively harvested forests of NS as well.

- Nova Scotians have a long history of recreational use of our forests for hunting, fishing and camping, and more recently for ecotourism, forest schools, “forest bathing”. Post-2016, our population began to increase very rapidly, and continues i.e., there will be more need for such uses of our forests in future, not less and such uses are largely incompatible with intensive harvesting.

- In 2021, our provincial government committed NS to 20% protection by 2030, it’s currently just under 14%. A major portion of the lands to be added to reach 20% will necessarily have to come from forested Crown lands – view Triad Land Distribution (page on this website) for some rough estimates of how much Crown working forest land could be involved. Also, we can expect in future that more forested lands in NS will be managed or co-managed by Mi’kmaw peoples with likely less intensive forestry overall than on private lands, re:principles of the Mi’kmaw Forestry Initiative.

- Current Crown land forestry accounting appears to significantly underestimate the areas where forest is harvested, e.g. by excluding forest removed to construct access roads and extraction trails in the Matrix Zone.*

*See Shady Accounting and Vanishing Forests on Nova Scotia’s Crown Lands Post on this website by Nina Newington Jul 14, 2024 - There are increasing demands to convert forested land to non-forest uses such as windmill megaprojects, roads, settlements.

I could go on. The point to be made is that citing the 2016 estimate of the Sustainable Forest Harvest level as representative of what’s available today, or of what could be sustained well into the future or of what Nova Scotians wish to be available for harvesting while allowing for other uses and values of our forested landscape is surely mis-representing the reality of today.

NEW DEMANDS ON THE NS WOOD SUPPLY

While current harvest levels are much lower than historic levels – and perhaps within sustainable levels from a purely wood supply perspective – the current production, plus that which would occur if a plethora of expectations/proposals/plans (some implemented) are realized could greatly exceed sustainable levels, especially on Crown lands. Chief among those expectations/proposals/plans:

– Housing/MassTimber. As elsewhere in Canada, there is a severe housing shortage in NS; what better use could we make of our wood supply than to build those houses? The $215 million mass timber manufacturing facility now under construction at the Elmsdale Business Park in East Hants through the collaboration of MTC (Mass Timber Company), Elmsdale Lumber, and Ledwidge Lumber is potentially a very positive development from both the production/manufacturing side and environmentally.

Once constructed, MTC will be Canada’s first vertically integrated mass timber manufacturer in Atlantic Canada, allowing further growth of the region’s offsite building construction sector and improving access to housing for Nova Scotians…Ultimately, this project would add value to the lumber products produced by the company in Nova Scotia, using next-generation technology to strengthen the forest sector in the province. – NRC News Release Mar 20, 2025

Lighter than concrete or steel but strong enough for use in load-bearing beams and columns, mass timber has environmental and construction virtues that could dramatically change the building landscape, green construction advocates say. – Darius Snieckus in National Observer Mar 8, 2024

Estimated annual lumber consumption for the facility has been cited as 43 million board feet*; In 2024 total lumber production in NS was 417,471,150 board feet (Registry of Buyers 2025). Reassurances that Mass Timber construction in fact results in more carbon capture than traditional wood/concrete & steel based construction are generally limited to the assumption that the wood is “sustainably harvested”. Thus it is critical that the NS Government provides credible, quantitative documentation of sustainable harvesting & carbon balances, at the very least, least for our Crown lands. View Mass Timber and NS Forest Biomass RRA 2024 (pages on this website) for more on the topic.

* Atlantic Forestry Review July 2024, page 27

– Forest Biomass for the Bioeconomy

The other major new demand, for forest biomass, is mostly anticipated and not in place at this stage. As elsewhere in Canada*, use of forest biomass to produce heat and electricity and a growing range of green products is viewed as providing both a replacement for sawmill wastes and low grade wood once purchased by pulp and paper mills that have now closed, and as a brand new market to supply feedstocks for a range of emerging biotechnologies. *Andrew Snook, New homes needed for industry’s residuals, Dec 23, 2025 in Canadian Biomass

The NS government is actively promoting use of wood for heating and “to leverage Nova Scotia’s forest sector to advance renewable resources and a sustainable bioeconomy”; the latter includes increased value-added through development and use of forest bioproducts, and advancing the production and use of biofuels and bioenergy*.

*See Nova Scotia Regional Energy and Resource Table – Framework for Collaboration on the Path to Net-Zero: Forest bioeconomy (Oct 22; last modified 2025-02-11

In Chart 7 below, I have compiled available estimates of the the forest biomass supply requirements for biomass-consuming entities in NS currently operating or being developed or seriously proposed/being considered.

Chart 7: Forest biomass supply requirements for biomass-consuming entities in NS. These numbers are based on public available info. Estimates will be revised as better data are obtained, or (preferably), government/industry produce authoritative, publicly available stats. Last Update: Nov 29, 2025. See separate page on this website for details, & related notes

| Entity | Current or Projected |

Green Tonnes per annum |

Comments |

| PHP [1] | Current | 750,000 | Heat &Electricity, 60 MW generator |

| Brooklyn Energy [2] | Current | 325,000 | Heat & Electricity 30 MW generator |

| Hefler [2] | Current | 40,000 | Heat & Electricity 3.7 MW generator |

| Dalhousie AC Campus Truro [3] | Current | 20,000 | Heat, and 1 MW electriciy generator |

| Taylor Lumber[4] | Current | 30,000 | Heat &Electricity, 1.5 MW; estimated |

| Shaw Resouces- pellets [5] | Current | 100,000 | Assume 2.1 Green Tonnes/Tonne Pellets |

| GNT- Pellets [5] | Current | 200,000 | Assume 2.1 Green Tonnes/Tonne Pellets |

| BDO SW Nova Scotia [6] | Proposed/Projected | 550,000 | SW Nova Scotia is an ‘A’ rated Bioeconomy Development Opportunity Zone. |

| Nova Sustainable Fuels (prev.Simply Blue) [7] | Projected | 750,000 | Green Hydrogen project |

| District Heating [8] | Proposed/Projected | 3,800,000 | estimate |

| Public Buildings Wood heat [9] | Current | 20,000 | estimate |

| Other [10] | Current | 100,000 | Guesstimate |

| Total | Current, Projected, & Proposed/Projected |

6,685,000 |

It appears that if we were to provide forest biomass to all of the entities above, it would require not only all of the waste wood from all our sawmills, but the entire forest harvest at the 2016 estimate of the Sustainable Harvest Level (5.7 million cubic meters/annum), and more! The District Heating proposal, implemented at full scale, constitutes more than half of the total.

CONCLUSIONS

I draw three major conclusions from the various considerations above:

(i) We urgently need authoritative, independently verifiable estimates of the sustainable wood supply in NS detailed by species, primary and secondary products, geographic distribution and ownership/administration.

(ii) Such estimates must take into account new risks, uncertainties associated factors that have arisen since 2016.

(iii) If we are to proceed producing biomass on a scale significantly above our current supply of genuine sawmill wastes, we should be looking at the potential for supplementing forest biomass with non-forest biomass including “use of purpose grown non-forest energy crops ([e.g.] grasses, fast-growing willow) on marginal farmland currently not being cultivated”.*

*From the Stakeholder consultation process for: A new renewable energy strategy for Nova Scotia, Final report to the government of Nova Scotia by Michelle Adams and David Wheeler, Faculty of Management Dalhousie University, December 28th 2009; available on the web archive (https://web.archive.org/web/20111123122527/http://www.gov.ns.ca/energy/resources/EM/renewable/Wheeler-Renewable-Stakeholder-Consultation-Report.pdf. See pp 42-43 which include estimates of how much biomass can be produced on marginal farm land. Also see Developing Switchgrass and Big Bluestem as easy to grow/low cost crops for the bio-based economy, Switchgrass as a Biomass crop; and Comparing biomass yields of various willow cultivars in short-rotation coppice over six growing seasons across a broad climatic gradient in Eastern Canada (by Michel Labrecque et. al, 2023 in Canadian Journal of Forest Research)

I am concerned that, currently, most of the lobbying and decision-making or explicit or implied commitments of forested land by both government and the big forestry players in NS are going on largely behind closed doors without public consultation and without reservations about the wood supply because no reasons have been given for such reservations; as well the Forest EA, a component of the Lahey Recommendations which would allow for the full set of stakeholders in our Crown lands to have an ongoing say at the landscape or “strategic” level of decision-making has evidently now been dropped.* *See On the WestFor 12-month plans & making the Nova Scotia Forest Triad work for all of us, post/page on this website, Dec 12, 2025.

Surely such lack of transparency does not serve Nova Scotians well; it generates concern that we could be making promises that can’t be kept, or that would require compensation payments if they are reneged upon, or that if kept, would significantly reduce our options for management of Crown lands in future: Nova Scotia has a history of making long term commitments or leases that have not served us well in their latter years.*

** See Against the Grain: Forestry & Politics in Nova Scotia by LA Sandberg and P. Clancy. 2000. UBC Press. Chapters 1 is available online; Forest Policy in Nova Scotia: The Big Lease, Cape Breton Island, 1899-1960 by L. Anders Sandberg in Acadiensis, 1991; Nova Scotia long-term Crown timber harvest leases still on hold, Paul Withers CBC News, Aug 24, 2018.

In the long run, hyping up the numbers could also prove to be bad for business, for the investors who view numbers coming from government without explicit qualification as fully credible.

ON THE WORK UNDERWAY TO DEVELOP A NEW NUMBER BASED ON THE TRIAD MODEL

Surely the NS government needs to move much more quickly in regard to the “Work [that] is underway to develop a new number based on the triad model.” Presumably the work underway relates to the next State of the Forest Report, about which Bill Lahey had clear recommendations. Following are excerpts from pages 65-66 in the Independent Evaluation of Implementation of the Forest Practices Report for Nova Scotia (2018)

by William Lahey, Nov 2021.

| Outcomes Evaluation

The third level of evaluation, and associated indicators, is about outcomes. The focus shifts from the activity underway to implement the FPR and the outcomes produced by that activity, to questions such as the condition of forests and the forest products available to industry plausibly resulting from implementation. But there are also other kinds of relevant outcomes.For example, what is the level of public awareness of and approval of changes happening in how Crown lands are managed, and do the public believe that the condition of Nova Scotia’s forests is healthy or unhealthy, improving or declining? It is also important to know the level of public trust and confidence in the Department relative to forestry in general and on Crown lands in particular, and with respect to the management of Crown lands more generally. The indicators needed for this level of evaluation in relation to the condition of forests are more challenging to identify because of the relative diffuseness of the outcomes e.g., healthier ecosystems and biodiversity and the complexity of attributing changes in observed conditions to implementation of the FPR. There must be clarity on the required attributes of indicators to ensure their quality and utility. Indicators must be developed in advance of their application in evaluation to ensure not only the objectivity of evaluation and therefore its reliability but also its feasibility and efficiency.It is anticipated that a significant number of indicators currently not in use may have to be tracked. This may mean collecting data that we do not currently collect.This raises issues about establishing the benchmark from which measurement can begin. Measuring the condition of the forests and of the wood supply should be among the purposes of the Department’s State of the Forest report. The FPR included specific recommendations (5 and 6) for improving the report and state of the forest reporting more broadly to ensure that it better achieves its intended purpose, as follows: 5. Whether the forests are in good, poor, improving, or declining condition regionally and provincially, both from an ecological perspective and as an economic resource should be the guiding question in discussions and decision making for forestry in Nova Scotia. To that end:

6. DNR should work transparently and collaboratively with interested parties, including representatives from the academic community, in making improvements to reporting on forests and forestry, including in the State of the Forest report. With the implementation of these recommendations, which is in early stages, State of the Forest reports should become the major data source for future outcomes evaluations. |

HOW ABOUT IT, PREMIER HOUSTON…

How about it, Premier & Minister of Energy Tim Houston, Min. Kim Masland (Natural Resources) and Minister Timothy Halman (Environment & Climate Change?

Will we see a State of the Forest Report and a brand new up-to-date, well documented, credible estimate of the sustainable forest harvest level for Nova Scotia in 2026?

I hope so.

RELATED

–Biomass could play a key role in Canada’s transition to a carbon-neutral economy. Normand Mousseau & Roberta Dagher in The Conversation, Jan 27, 2026. Some extracts, bolding inserted.“Canada needs to move towards a carbon-neutral economy, and the biomass sectors have a key role to play in this transition.The availability of diverse biomass resources in Canada’s forests and agricultural lands, combined with new technologies to convert them into bioproducts and bioenergy, makes biomass a potential solution for reducing carbon emissions in several sectors, including industry, construction and all modes of transport (road, marine, rail and air). Biomass can be part of climate change mitigation strategies. Used properly, it can replace fossil fuels and products, and help store carbon in different ways: in sustainable materials made from wood or agricultural residues, in the form of biochar that traps carbon in the soil or through bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), which prevents carbon released during energy production from entering the atmosphere…

The potential role of biomass becomes clear in the pathways now being modelled to achieve Canada’s climate goals. These analyses show that if a significant portion of available biomass were used differently, it would be possible to sequester up to 94 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per year through BECCS and biochar. These results underscore the need for Canada to carefully plan new project developments and judiciously allocate biomass between its traditional and emerging uses. Best uses for biomass.As we explain in a recent study, several factors influence the potential of biomass to reduce emissions, including the type of ecosystem where it’s harvested, the efficiency of its conversion, the fuels used and the products it replaces in the sectors concerned…Using biomass effectively requires understanding what resources will be available under climate change and their true potential to cut emissions. That potential depends not only on technological efficiency, but also on the cultural, environmental and economic realities of communities…

Yet, despite the importance of its resources, Canada has no strategy or vision for the role biomass will play in the transition to carbon neutrality by 2050. Canada has developed several bioeconomy frameworks, including the Renewed Forest Bioeconomy Framework (2022) and the Canadian Bioeconomy Strategy (2019). However, there is still no comprehensive strategy that defines the role biomass will play in achieving a carbon-neutral future, either in energy-related or non-energy-related sectors…Biomass cannot be managed blindly. Its impacts vary depending on the region and uses. For future projects to truly contribute to Canada’s climate goals, a coherent national vision is needed now.”